WINNER OF THE 2008 BEST BOOKS OF INDIANA AWARD FOR FICTION!

IN STORES NOW!

CLICK HERE TO BUY!

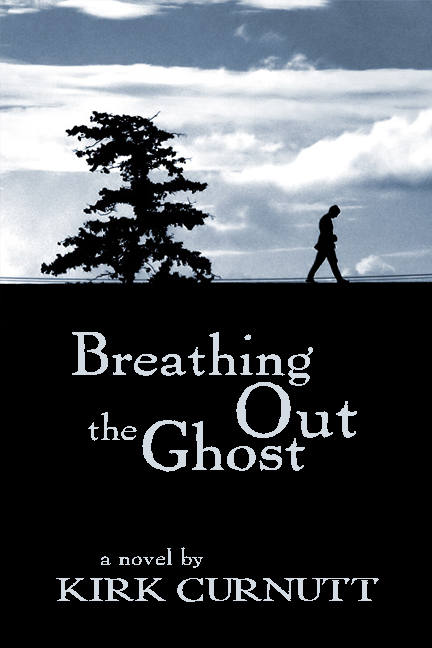

Colin St. Claire is on a dangerous mission. His young son is missing, and he is on a self-appointed quest to find the boy, or at least find the man he believes is responsible. Fueled by uppers and a profound lack of sleep, Colin’s road soon becomes an uncontrollable spiral of blurry white lines, of fleeting forms in the night, ghosts of memory as intangible as vapor . . . Assisting him is Robert Heim, a former private investigator who lost his license in the line of duty—and it is a sense of warped duty that still ties him to Colin, though his own family, a loving wife and children, beckons him back home . . . The answers for both men may lie not with the man they believe is the perpetrator, but with a long-suffering farmer’s wife, Beverly “Sis” Pruitt, whose own daughter was claimed by violence, years prior.

In the shape of a noir thriller, Curnutt fashions a gripping tale of the consequences of unchecked grief, of painful truths hidden as though they were dark secrets, and what salvation remains possible for good men who enter the darkness and become the ghosts they are chasing.

"The writing is unobtrusively brilliant... See for yourself."

---George Garrett, Poet Laureate of Virginia

from the chapter "In Nomine Diaboli":

Have you ever wondered what would’ve happened to Ahab had he gotten his whale?

Say that in those last moments of the chase he hadn’t got caught in the harpoon line. Say he hadn’t been jerked neck first into the wake to become a dangling fob at the end of his own barb. Say he and his madman crew managed a fatal lance that laid his enemy to waste. Imagine the joy that would spread across his scarred face as he danced a jig atop the carcass, his peg leg defiantly wedged in the blowhole. Imagine the wad he’d shoot as he watched the blubber stripped and boiled in the try-pots. What next? How would he get back to the land of the living? He’d head home to Nantucket. To love his wife. To be happy. To raise his boy.

It’s a detail little remarked upon, you know, that Ahab had a young son.

Or more apropos of us, to you and me, A. J.: what if he hadn’t been bowstrung, but the flying turn still tore astray of its groove. What if the eye-splice knot at the rope’s end still shot straight out of the boat so the whale was able to slip away, wounded but not willing to let itself get carved into decorative candles for landlubbers. Imagine the old man’s dismay as he sees the thing spasm and yet escape, leaving only a trail of chum swirling in the backwash. How could he return to the land of the living then? He’d row away, go home. He’d brag about his deeds to the old salts in the beer stalls. He’d assure his wife he had straightened out his soul. At night he’d creep into his son’s room and whisper in the boy’s ear: I did it for you. And yet he’d never be able to just be content. Because if he were, he’d have to be normal.

Could he even? Once he stood, a mighty speck on an ocean, daring the lightning to strike. Now he’d have to contend with a wife who wants to know why he thinks he’s too good to take out the trash. He’d probably end up staring at the sea, misty-eyed, recalling how the anger once gave his life purpose. I hear him saying, “Happiness is like the horizon of calm water days—infinite, awesome, tedious. Where’s that razor’s edge that I used to walk?” That’s why the story ends the way it does. It has to. Anything less would disappoint the drama.

At least that’s what they’d have us believe. To be alive, really alive, you must bear the burden of being deep. Lug that cross of discontent. Do you know, little man, the first emotion in all of literature? Call it what you will: wrath, rage, ire. Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles, son of Peleus, that brought countless ills upon the Achaeans. Many a brave soul did it send hurrying down to Hades, and many a hero did it yield a prey to dogs and vultures, for so were the counsels of Jove fulfilled from the day on which the son of Atreus, king of men, and great Achilles, first fell out with one another.… That’s The Iliad. Go look it up. But if the reference is too arcane for you, remember the song with the slinky riff that I used to pluck out on the guitar. The best line in the whole thing: I wish I was like you—easily amused. What a devastating putdown for those without the misery to love company. Yes, it was once quite nice to think that shallow people had it easy. No needs, no wants, no problems. And that we, by contrast, were special because ... why?

Because we could never settle, could never compromise. Perpetual disappointment was a sign that the needles of our machinery were more finely tuned. It meant we were sensitive. Like a seismometer, we were privy to those faraway vibrations that lesser folks could never detect.

From the chapter "Mother Comforts":

“That was a dirty trick,” she whispered when she caught up to the sheriff at the head of the food line. “Just because you’re making Pete stay here all day doesn’t mean I’m going to. I can’t, Dub. I need to walk this off.”

The sheriff peeled the cupcake paper back on a sausage muffin. “I was half expecting a call from you last night. You and Pete are the only folks to know what it’s like firsthand to wait through one of these searches. There are things I might never think of that the Birmages ought to know to expect. I was so surprised you didn’t call that I called home and asked Cinda if I ought to try you. She told me not to. Cinda said if you didn’t call then it was your way of saying it was asking too much.”

“You wouldn’t have wanted me with the family. The news brought back too many feelings. Once I heard the search was based from here, this same church, I was too upset. So many things were so suddenly fresh. I had to take Tillie and Joey to my mom and dad’s so I could work it through.”

“You know why we chose this church as base. We’d be here if it was a tornado or any other kind of emergency. It’s the same reason we were here seventeen years ago: the church is centrally located and it has the biggest congregation in town. I have to consider logistics, even at the cost of feelings."

“I’m not criticizing. I’m not asking for folks to dance around me either. I’m only saying I’ll be more help if you let Pete and me go out with the others instead of making us stay with the family.”

“You don’t think it’d be hard for you out there as well? We’ve got to follow the creek, Sis. That means we’ve got to cross Greensburg Road by Smiley’s Mill, and that’s not a hundred yards from the very spot.”

“I drive past that spot any number of times a week. I still shop at Smiley’s from time to time. I probably see that cornfield more than I see Patty’s grave, but I can do that because at some point it became routine. Maybe I could smile and dispense hugs and tell the Birmages everything will be okay if I’d been to this church once in the past seventeen years, but I haven’t. I never came back here because I never thought I’d have to; I never wanted to come back because I wanted at least one site within the circumference of my life that I didn’t have to get used to walking into normal-like so I could remember that since that day my life hasn’t been normal at all. This place is like sacred ground to me, Dub, but the last thing this family needs is to see me walking backwards through a decade and a half. Shiloh Baptist has plenty of women who’re better comfort givers.… Look at how much comfort food they rounded up on such short notice.”

“I know this isn’t easy on you and Pete, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy on anybody else. A lot of folks are having flashbacks.…”

“I know that. I know I’m here to calm those flashbacks, quell them even. I’m not sure I can, though, when I feel like I’m drowning in my own.… Do you know Pete’s way of keeping his head above his memories? He tilled soybeans until nine o’clock last night—way past dark. He’d be at the bottomland today except he knows it’d look odd if we weren’t here.”

She saw Dub’s eyes widen a bit; she wondered if that was his reaction when a suspect ratted out a conspirator without any prodding.

“Now see, that’s why I needed you yesterday. I could’ve used your help as much as the Birmages. Maybe not even help, just advice. There are things I’ve been taught to look for in situations like this. They’re things that are supposed to be clues, but I don’t think I’m good at catching them. I guess I’m too gullible; the criteria for clues have always struck me as faulty. I was trained to think that if somebody isn’t grieving like I suppose they ought to, that’s a sign to get suspicious about. I was never quite clear on what exactly ‘ought to’ means, though.”

“There is no ‘ought to.’ ‘Ought to’ is what other people insist on to stable themselves.”

“I don’t disagree, even though I suppose I’m as guilty of it as anybody. Last night I was sitting with the grandmother when the mother comes waltzing into the parlor with a beer. If I’d followed my instincts, I’d have said that wasn’t the right way to behave when your boy is missing, that it might be an indicator even. Only I already knew there was nothing really wrong with it, other than it made me uncomfortable as hell. Awkward isn’t illegal, and beer isn’t evidence of anything, any more than tilling soybeans is. Especially when the mother’s already passed her lie detector.”

“What about the father? Have you tested By-God yet?”

Dub squeezed the empty cupcake wrapper in his fist. When he couldn’t find a garbage can he tossed the wrapper next to a plate of crisp sausage links, his lips wrenched flat with a forced smile.

“You don’t even realize that’s the talent you’ve gained from what you’ve gone through, do you? You give better comfort than you care to think; you right near cast a spell with it. Here I am talking out of turn, damn near spilling secrets I shouldn’t be, and all because of how you’ve soldiered on. Your strength is disarming—it makes people want to confide in you. That’s a gift, I recoken.” He glanced at his watch. “You’ll excuse me now. I’m looking down the barrel of a long day.”

She saw him glance east, where State Road 44 led out of Franklin into the countryside. It was only then that Sis realized how much territory the search had to cover: Sugar Creek ran for forty miles.

“I’ll do what I can for the Birmages, but there’s something you need to know.”

The sheriff’s eyebrows warily shot up, and all forty of those creek miles seemed to be etched in the creases of his forehead. “What should I know, Mrs. Pruitt?”

“You reckoned wrong. It’s never felt like a gift. Not once.”

She had made her point but it didn’t make her feel any better. The fact that Sis felt compelled to make a point at all embarrassed her. Dub had no sooner walked off than she wanted to pull him back and clarify. She wanted to explain that grief to her wasn’t always easy to distinguish from vanity: it led you to believe that you had a certain authority over other people, that you were special. It wasn’t entirely your fault either—other people encouraged that attitude. They didn’t know it, but they fed it by treating you as if you had some wisdom to impart, a lesson to teach. As Sis watched Dub urge the volunteers to wrap up their eating, she asked herself what being the parent of a murdered child had taught her. The answer was nothing—nothing except the inexhaustibility of her own anger, anger at never not being reminded of what she’d lived through, what she’d always be living through, and most of all anger at the presumption that she should be over it, that she should have at some point overcome, have triumphed and proved, if not for her sake then for the sake of those around her, that life goes on. That was never the hard part, Sis thought. Life went on anyway, whether you wanted it to or not. The hard part was being left behind to breathe out the ghost of the one who’d gone on. |

|